What is one thing that makes transit great? It’s ability to move large numbers of people efficiently – far more than just about any other form of transportation.

The Job of Your Streets

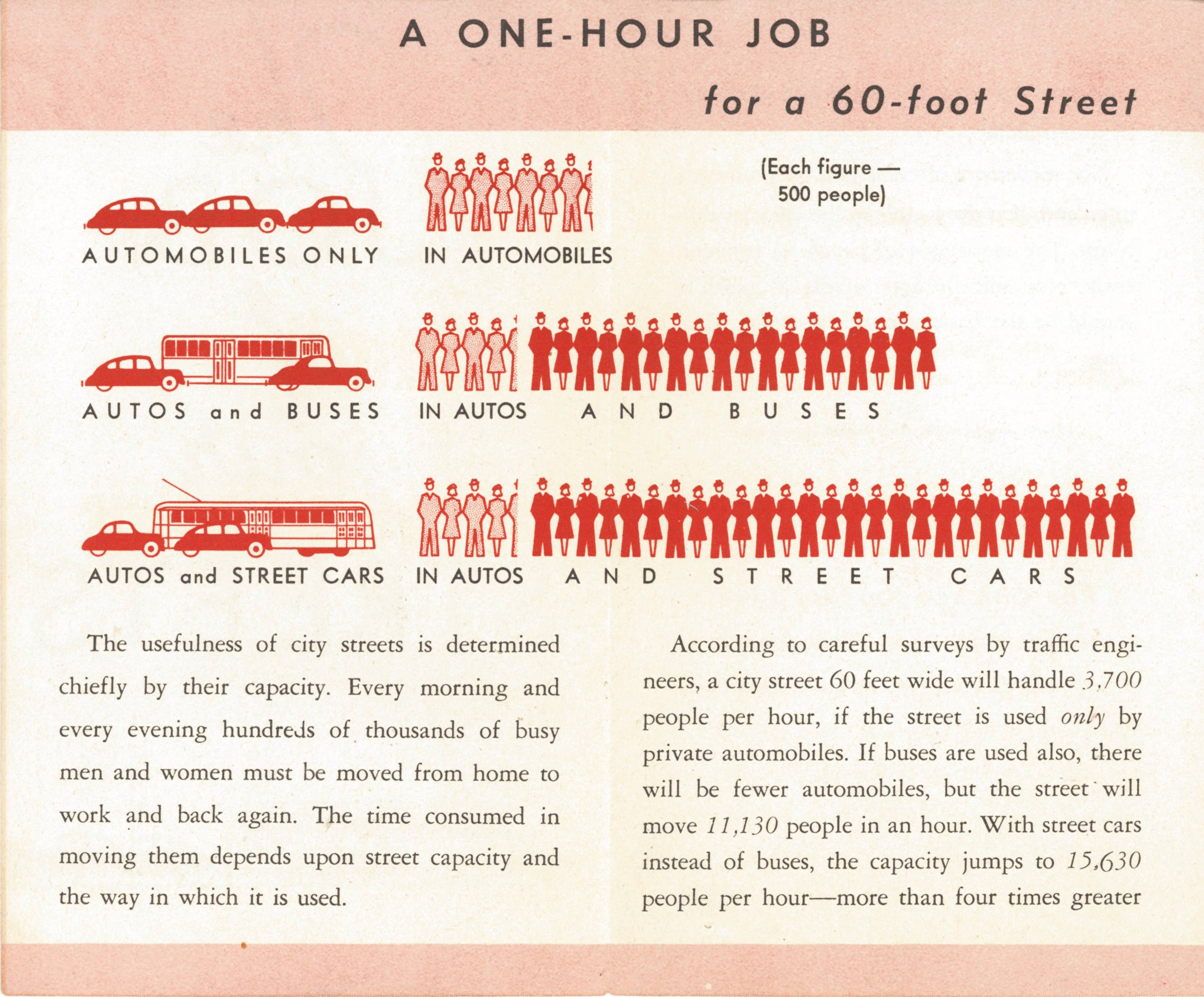

Long ago, we understood the value of transit’s space-efficiency. Check out this simple leaflet from 1940 from the Chicago Surface Lines, once the operator of the largest streetcar system in the United States. Entitled “The Job of your Streets,” the leaflet argues that compared to travel by a private automobile,

- Buses can effectively tripling the street’s capacity on a 60-foot wide street, and

- Streetcars can effective quadruple the street’s capacity

While the absolute numbers cited likely reflect ideal conditions with intensive transit service on a busy downtown street, there is no question about the carrying-capacity value of transit:

The movement of vehicles is only a means to an end. It is the people in the vehicles that count.

The Job of Your Streets, Chicago Surface Lines (1940)

(Source: Chicago Surface Lines (1940), Credit: Jason Lee)

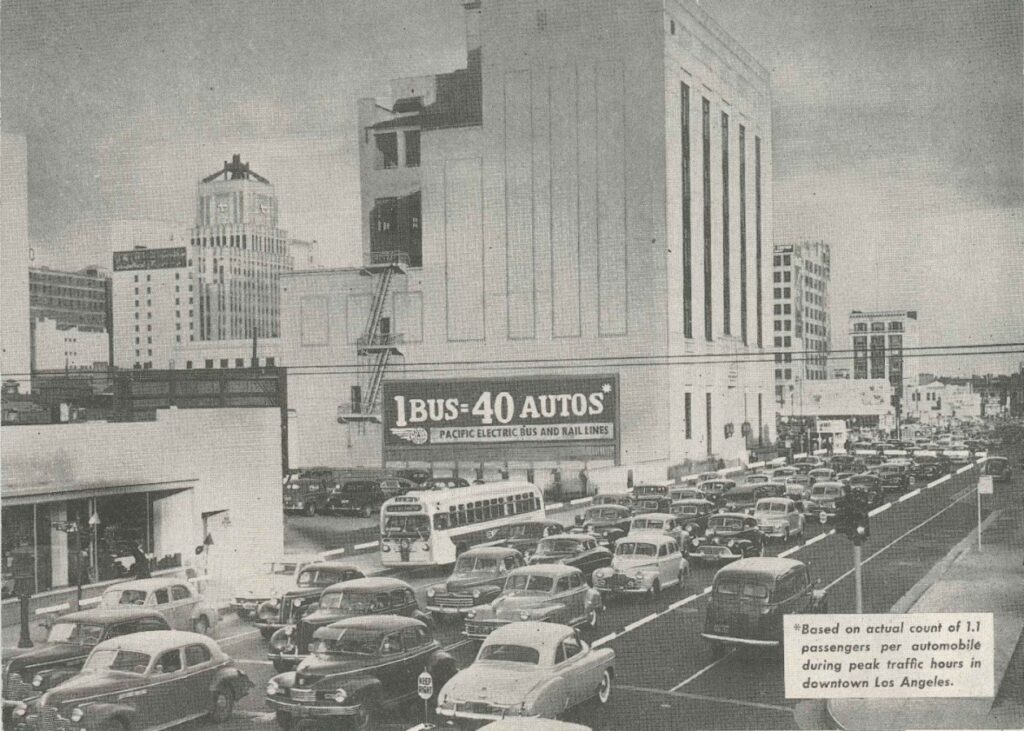

Two-thousand miles to the southwest, Southern California’s Pacific Electric Railway compared the footprint of a bus and an equivalent number of cars on a Downtown Los Angeles street. Compared to a bus, forty cars overwhelmed the street, causing a traffic jam. Pacific Electric trains could carry even more people than a bus – rail cars could seat 60 or more people and multiple cars could be coupled together in trains. The footprint of a train and an equivalent number of cars would have stretched beyond the photo.

(Just a year after this photo was taken, Metropolitan Coach Lines acquired the Pacific Electric Railway. Unfortunately, the new leadership was associated with National City Lines, a holding company comprised of automobile, tire and petroleum interests. Within a decade, electric trains had disappeared from Los Angeles.)

(Source: Pacific Electric Railway (1952), Credit: Jason Lee)

Then there is the question of where to put all these cars once people have reached their destinations. Car storage space, also known as surface parking or parking garages, takes up valuable land that could otherwise serve retail, employment, housing or other purposes.

For at least eighty years, we have known these basic spatial facts. Nonetheless, the country has put most of its public resources not in the most space-efficient form of transportation, but in the least space-efficient one. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, popularly known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, which funded the interstate highway system perhaps most symbolizes this policy. The vast majority of these highways are free to use, despite requiring vast resources for construction and maintenance and socializing costs for environmental damage and climate change. The subsidization of the automobile has extended to state and local levels through massive road building and free parking, while transit was allowed to deteriorate.

New Technology Does Not Diminish Transit’s Space Efficiency Advantage

In the 2010s, this country became allured by the promise of self-driving cars and ride-hailing. Some estimates have put research alone into self-driving vehicles at $16 billion. Meanwhile, Uber has become a ride-hailing behemoth though it lost $8.5 billion in 2019 despite many of its drivers effectively earning less than minimum wage.

Even Car and Driver, a magazine for automobile aficionados, described the financial and logistical challenges facing self-driving cars and ride hailing.

“The point is that it’s very expensive to make self-driving a reality, and when it does happen, these companies are going to spend years trying to pay off the research and development that’s needed for a robot to chauffeur you around town. If you look at Uber and Lyft right now, their ride-share business plans don’t actually produce a profit. Robo-taxis could reduce the cost of each ride in the future. But that’s a ways off, and it’s going to be quite a while before a car picks you up and drives you to your destination without any human involvement, whether in the car waiting for something to go wrong or controlling the vehicle remotely.”

“Self-Driving-Car Research Has Cost $16 Billion. What Do We Have to Show for It?”, Roberto Baldwin, Car and Driver, February 10, 2020

Putting aside these financial issues, self-driving cars and ride-hailing are still cars. So are electric cars. Cars take space. Car storage also takes space – whether it is parking or “storage in motion” where self-driving or ride-hailing cars are repositioning themselves between riders. Ultimately, this is not a scalable solution for human-friendly streets and sustainable cities.

Technology fundamentally does not alter what we have known since at least the 1940s: that transit is an incredibly efficient and effective use of public space, applicable even in pandemic times with physical distancing between riders. This is a great value of transit – one of many that justifies its public support regardless of whether someone rides transit or benefits indirectly from it.